Progressive Education at Sequoyah

Progressive principles of education were first articulated in the late 19th century by school reformers, like John Dewey, Carter G. Woodson, Helen Parkhurst, Rudolf Steiner, and others who countered the industrial factory model with a call for educators to create schooling that would prepare children to become active, engaged critical thinkers and lifelong learners – fostering those skills and habits of mind that were seen as necessary for citizens in a democratic society.

- Child-centered: prioritizing the needs and interests of children

- Building an authentic desire to learn: student ownership of their learning

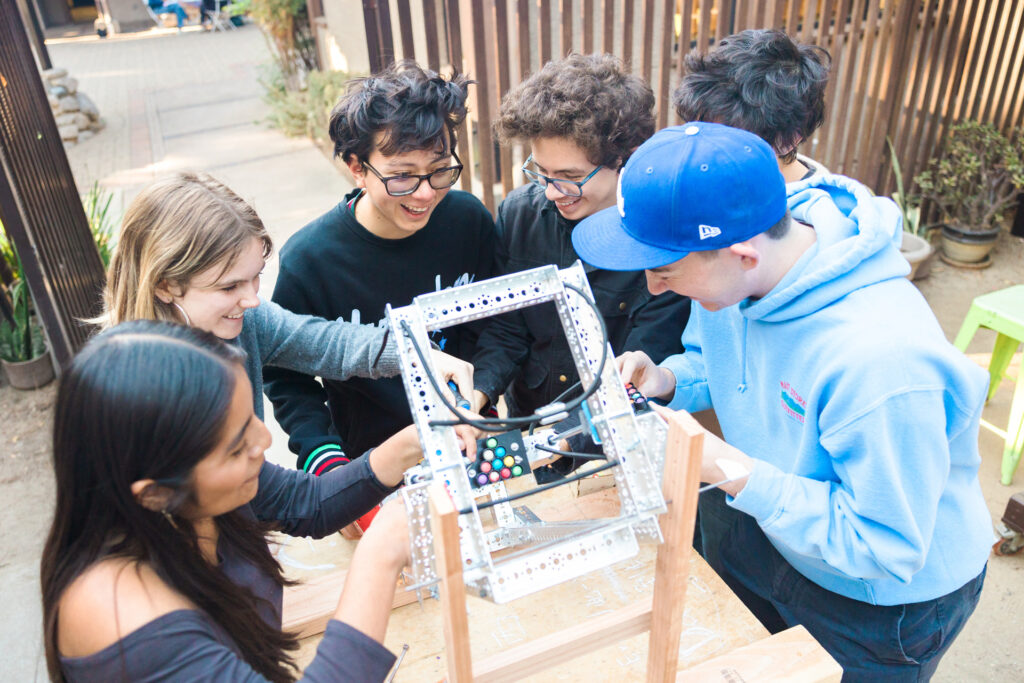

- Experiential Learning: active project-based model with intentional integration

- Critical thinking: how we think and care about issues that matter

How is progressive education put into practice at Sequoyah?

Student ownership of their learning experience is key.

Our classrooms can be active busy places with a lot of energetic conversations and then shift to become quiet contemplative study areas for independent work. What is constant is the careful encouragement to step up to an intellectual challenge, venture an opinion, try something new – and each child is encouraged to go on her own journey of discovery, with plenty of guidance along the way.

From a kindergarten student presenting their “About Me” project, to an 11th grader delivering a talk on climate change and the challenges of the media, students apply knowledge creatively, collaboratively, and critically to take ownership of the issues that matter to them, and share their ideas with their community. Assessment and feedback serve to support the student to set their own goals and reflect on their progress. Engaging students in their own learning is as relevant today as it was when John Dewey first began to inspire educational reform.

"Because they are asking why, they practice becoming actively discerning. That is our hope — that our students ready themselves to participate in their communities with knowledge, compassion, and ethics."